Data show that countries that empower women tend to see lower rates of stunting, a measure of chronic undernutrition. Use this interactive tool to explore the data and build your own scatter plots.

All posts by hans

Andrea James has fought for justice within the criminal justice system for more than 25 years, including many years as a criminal defense attorney. But in 2009 she was disbarred and sentenced to a 24-month federal prison sentence for wire fraud. Even after a career defending the rights of disenfranchised people, she was stunned at what she saw upon entering the federal prison system.

“During my incarceration I was deeply affected by the great number of women who are in prison,” Andrea said. “Most of these women are serving very long mandatory minimum or guideline sentences for minor participation in drug possession or sales. Most of them are mothers. Their sentences are unreasonably long, the average being 10 years. They have been in prison long after what should be considered fair sentences while their children, left behind, struggle to survive.”

Andrea has committed herself to fulfilling the promise she made to women who remain in prison. Families for Justice as Healing (FJAH), the organization she founded in 2010 inside the federal prison for women in Danbury, CT, brings formerly incarcerated women together to be part of a movement to create alternatives to incarceration. FJAH rejects U.S. drug policies that prioritize criminalization and incarceration, advocating for a shift toward community wellness. The organization believes that to seriously confront drug-related illness, crime, and violence, the nation’s leaders must commit to evidence-based solutions that address poverty, addiction, and trauma.

When Andrea was released in 2011, she carried FJAH back to her home community in Roxbury, MA. Since then, FJAH has been active in building coalitions, advocating in legislatures, and raising awareness among policymakers of the need to end the War on Drugs. From national rallies to summer camps for girls, FJAH is continually expanding and evolving. On June 21, 2014, FJAH led the FREE HER rally on the National Mall in Washington, DC. People from across the country used their collective voice to raise awareness of the devastating impact that overly harsh drug sentencing policies have had on women and their children and how mass incarceration and the War on Drugs has directly impacted communities.

Photo Credit: Joseph Molieri/Bread for the World

Starting at an early age, Patience Chifundo saw no reason a Malawian woman should be denied the same opportunities as a Malawian man. Her mother embodied this principle. She owned and drove a minibus, an unusual occupation for a woman in this country.

Patience saw the discrimination women faced in Malawi but had experienced little of it herself until she was a student at the elite Chancellor College and ran for student president. She had always been a precocious student and started college at the age of 15. Tradition is held in high regard at Chancellor College, and no woman had ever run for student body president. Patience did not win the election, but the discrimination she experienced as a candidate was a life-changing experience. When it became clear to her opponents—all of them male—that she had a formidable intellect, they agreed to all support one of their number who had the best chance of winning against “the girl.”

After graduation, Patience joined the Young Politicians Union, an organization of people from her own generation as passionate as she was to invigorate political debate in Malawi. She describes her experience with the Young Politicians Union as the practicum to her classroom education in political theory at Chancellor College. Most of the other women affiliated with the organization had none of the background in political theory that she did. These women came to meetings with nursing babies and little else besides bus fare home. They inspired her and through them she learned how politics actually works at the grassroots level.

One such woman is Annis Luka, a subsistence farmer from the Phalombe district in the southern region of the country. When Annis finished secondary school, she could not find a job and was forced to return home to farm with family members. She lives with 12 family members, including her parents, siblings, and a 7-year-old daughter. They grow maize, rice, sugar cane, and groundnuts, but do not earn enough to provide a buffer against the annual hungry season.

When students at Chancellor College needed to raise money for an event, they invited political leaders, candidates, intellectuals, and artists to speak or perform, and they could count on a paying crowd. Annis funds her activities by dedicating a share of her maize production to pay the expenses, but first ensures that no one else in the household has to go hungry to support her political work.

The intergovernmental agency Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance recommends: “Invest in leadership development and mentoring, especially for young women. Strive to make politics an accessible arena for low-income women and women from rural areas, whose representation has been constrained by the high cost of campaigning.”

Photo credit: Patience Chifundo has political ambitions, but believes Malawian women of her generation still face many disadvantages being accepted as capable leaders.

Photo Credit: Todd Post/Bread for the World

“India has nearly 1.5 million elected women representatives at the local level—in terms of numbers, this is the highest globally,” says Anne Stenhammer, program director at the South Asia Sub-Regional Office of UN Women. “However, even more important than the numbers is the issue of actual leadership and action on women’s rights.’’

The actual leadership and action is certainly what matters, but it is the fact that one-third of the seats on village councils are reserved for women that creates the opportunities for leaders to emerge.

Many of the women who’ve been elected to village councils have little formal education. But that doesn’t prevent them from championing education for girls. The women understand that it was their own parents’ attitudes that education for girls is not valuable that prevented them from continuing past the early primary grades of school.

Since the reservation policy went into effect and women reached more of a critical mass in the village councils, female members have made it a priority to dispel such prejudices. As one elected representative put it, “I hold meetings with parents, mostly mothers, in small groups and try to explain to them that if they do not educate their daughters, their fate, too, will be sealed like them and the vicious cycle of struggle for survival will continue for generations together. Their daughters will remain shackled by household work.”

When representative Radha Devi visited the secondary school in her village, she found girls carrying buckets of water from the hand pump outside the compound to the kitchen for preparation of the school’s mid-day meal. This seemed odd because the school employed workers for this task—and because while the girls were carrying water, boys were at their desks receiving instruction. The girls told Radha that if they objected or refused, the principal threatened to fail them. She confronted the principal and said in no uncertain terms that he must stop making the girls carry water, or he would be dismissed.

“I realize the importance of education,” said Radha, whose own formal education ended at grade 5. “The government is doing so much for education so it becomes our duty to make sure that nothing comes in the way. There should be no discrimination in schools, and in the last three years since I have been the sarpanch [the village head], I have made sure this doesn’t happen in my village.”

(Photo Credit: UN Women/ Ashutosh Negi)

Eduardo Munyamaliza, Executive Director of Rwanda Men’s Resource Center (RWAMREC), shares a story of how the women at the health clinic where he brought his child took pity on him. He was the only man among 300 to 400 women there with the children on the designated vaccination day. The women thought he must be a widower. When they learned that was not the case, they advised him that his wife must have bewitched him. Eduardo shares this story because it not only says something about the women’s attitudes, but it also explains why men would feel self-conscious or embarrassed about bringing their children to the clinic.

RWAMREC was formed to help men cope with these emotions and encourage them not to reject the natural caregiving urge they feel. Its objectives are threefold: inspiring men to become full partners in maternal and child health, empowering fathers to raise daughters and sons equally, and reducing gender-based violence. RWAMREC is spearheading the MenCare campaign in Rwanda. Now operating in more than 20 countries, MenCare was launched in 2011 by the Sonke Gender Justice Network and Instituto Promundo, nongovernmental organizations founded in South Africa (2006) and Brazil (1997) respectively.

Women and men both stand to gain as gender inequalities break down. But that message is not usually shared with men. Gender equality seems like a zero-sum game, with men expected to make concessions but receive nothing in return. “The norms are there to protect a man’s privileges,” says Eduardo of RWAMREC. “If you tell him to give these up, what are you giving him in its place?”

What men stand to gain by participating more in caregiving are happier, closer relationships with their wives and children. Beyond these less tangible benefits, men’s own mental and physical health will improve as maternal health-related outcomes improve and child development outcomes improve.

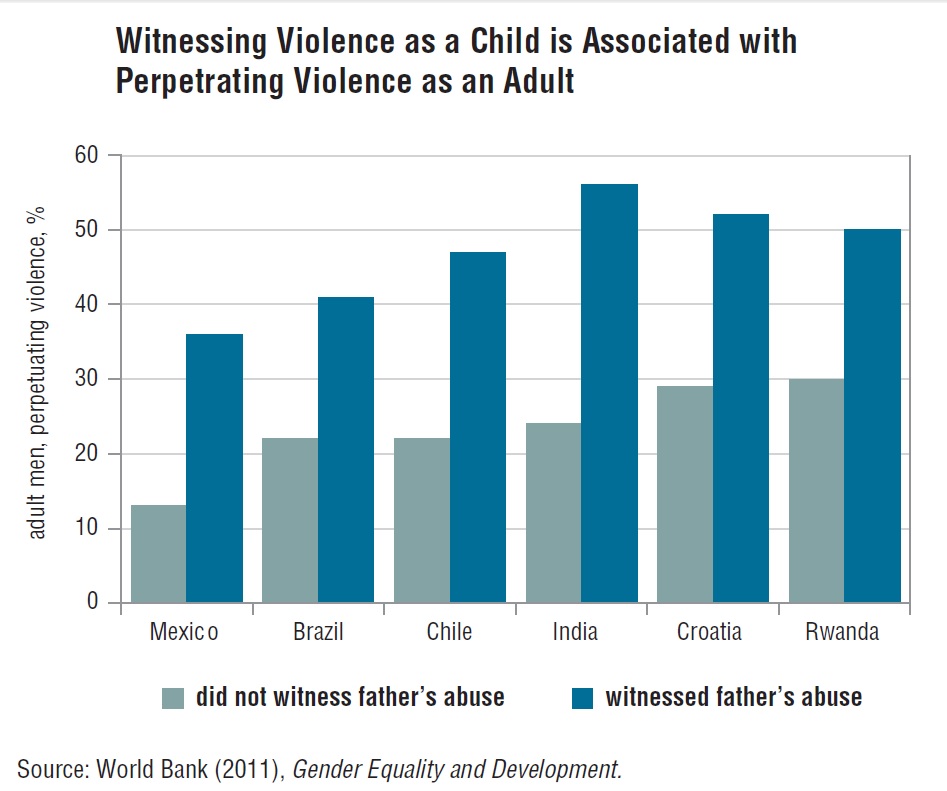

When men do not see how they gain, women become vulnerable to reprisals. Men who already feel marginalized economically may attempt to hold onto their role as head of the household more tightly than ever and lash out against what they experience as one more form of humiliation. A multi-country survey of more than 15,000 men in 10 countries—the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES), coordinated by Instituto Promundo and the International Center for Research on Women—found that men who commit violence against women “tend to buy into stereotypical notions of masculinity.”

Bread for the World Institute spoke to a participant in the MenCare campaign in Rwanda who discussed his transformation. His father was a violent man who had ruled the household by force during his childhood. Although he was not a violent man like his father, he thought of his role as strictly providing his wife with financial support to manage the household. He used not to think it was his responsibility to accompany his wife on visits to the clinic. But he was there with her when their son was born. He had felt conflicted about what seemed to be expected of him as a man in caring for his wife and child. MenCare helped him to realize there is no shame in wanting to hold his baby. He now bathes the baby. He even sings to the baby, something his father would never have done.

In July 2014, President Obama hosted a Town Hall meeting for 500 Mandela Washington Fellows who had come to the United States as part of the U.S. government’s Young Africa Leaders Initiative (YALI). These are some of the best and brightest people between the ages of 25 and 35 on the African continent, and in the Town Hall meeting they did not shy away from challenging the president on how the United States could be a stronger partner with their countries.

Changu Siwawa, a young woman from Botswana, said to the president, “I just wanted to find out how committed is the United States to assisting Africa in closing gender inequalities, which are contributing to gender-based violence and threaten the achievement of many Millennium Development goals.” The president responded, “Everything we do, every program that we have—any education program that we have, any health program that we have, any small business or economic development program that we have, we will write into it a gender equality component to it. This is not just going to be some side note. This will be part of everything that we do.”

Changu Siwawa understands the connection between gender-based violence and hunger all too well. She is the Outreach Coordinator for the Kagisano Society Women’s Shelter in Botswana. When she asked the president about the U.S. commitment to help Africa in closing gender inequalities, she highlighted the need for U.S. development assistance to strengthen African countries’ efforts to end violence against women.

Local NGO capacity building is one of the most important ways for U.S. development assistance to support partner countries. It is up to people from the country and the cultures concerned to figure out how to end gender discrimination. No one else can, despite how ubiquitous gender inequality is around the world, because the inequalities are highly situation specific and embedded in culture. Thus, the United States can be a more effective partner with Botswana by providing support to build the capacity of institutions such as women’s shelters, schools, and government offices so that they are able to succeed in closing gender inequalities in their country.

The Kagisano Society Women’s Shelter is an example of how U.S. development assistance can support the building of such local capacity. The shelter is funded in part by the U.S. President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Botswana has one of the highest HIV/AIDS rates in the world, and the web of connections among HIV/AIDS, sexual violence, and poverty is omnipresent there. PEPFAR supports the work of a Peace Corps volunteer at the Kagisano Society Women’s Shelter. Danielle Tuft has a master’s degree in public health and was placed at the shelter to work on capacity building. She assists Changu in outreach to children through school-based programs, developing a curriculum that gets primary- and middle-school students to reflect on the power relations they witness in their homes between mothers and fathers, and on how those relations are shaping their own experiences with the opposite sex.

U.S. government assistance has also provided technical support for the creation of a national database of victims of domestic violence, which Kagisano Society Women’s Shelter is using to identify people to refer to services such as health care and food assistance. U.S. development policy gives PEPFAR the flexibility to broaden its mandate to include disentangling the complicated web of connections among HIV/AIDS, gender-based violence, and hunger. U.S. assistance also provided a space for Changu and other young African leaders to come together in Washington, DC, where they founded a pan-African alliance against gender-based violence.

Odalis provides childcare out of her home in Syracuse, New York. Odalis and her family arrived in the United States from Cuba in 2002. Syracuse receives approximately 1,000 refugees per year and is one of the main resettlement locations in New York, the third largest resettlement state in the nation.

The West Side Learning Center in Syracuse, New York, serves new immigrants to the city, providing English language classes and training programs to help families adapt to life in the United States. The center not only provides childcare to the families learning English but also trains women who are interested in making a career of childcare.

Soon after moving to Syracuse from Cuba in 2002, Odalis Gaskins-Ginarte began both English classes and job training that helped her become a licensed childcare provider. Today, Odalis is a member of the Voice of Organized Independent Childcare Educators (VOICES), one of 7,200 registered group childcare providers in Local 100A of the Civil Service Employees Association.

When she left Cuba with her husband and 2-year-old son, Odalis was not expecting to make a career of child care and early childhood education. In Cuba, she was an architect. The skills she acquired as an architect in Cuba she puts to use every day teaching the children under her care. Odalis is more than an example of a refugee who transitioned to a successful second career. She has found not only a career but also a calling in childcare and early education. The United States may have lost a trained architect, but the country gained a committed nurturer and advocate who is helping both her new city and refugees from all over the world.

As a leader in her local union, Odalis speaks not only for herself and the other childcare providers, but also families of the children whom they provide care. It’s not that immigrant families can’t speak for themselves or don’t have the skill; parents are mostly struggling to make a living and scarcely have time to lobby elected officials. In recent years states have shifted more of the cost of child care to parents, due to budget shortfalls in the wake of the Great Recession and the federal government’s own cuts to childcare assistance. The bargaining power that comes with being part of the union has made it possible to forestall attempts to cut government assistance for child care.

Among childcare workers across the nation, just 6.2 percent are members of a union. Unions clearly benefit workers and women workers in particular. During the period 2009 to 2013, according to a study by the Center for Economic and Policy Research, women workers in unions earned an average of 12.9 percent more than nonunion women. But for women in typically low-wage occupations, the union-wage advantage is even larger—for example, 24 percent or $2.75 per hour for childcare workers. The study also found that companies with a union presence are 18 percent more likely to provide paid sick leave, 21 percent more likely to provide paid vacation, and 21 percent more likely to provide paid holidays.

“The Equal Pay Act is often presumed to be an accomplishment of the feminist movement of the 1960s. In fact, it was spearheaded by female trade unionists, who first introduced the bill in 1945 as an amendment to the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act,” says Ruth Milkman, a sociologist with City University of New York. “The bill was defeated, largely because of staunch opposition from business interests, but a coalition of labor activists reintroduced it every year until it finally passed in 1963.”

Belonging to a union does not eliminate the gender wage gap, but it does reduce it by half.

Union membership as a whole has been on the decline for more than 30 years, but this is more the case for men than for women. Women have a bigger stake than ever in the survival of unions and their continued ability to protect workers’ rights. At the time the Equal Pay Act was signed, women made up less than 20 percent of the union workforce in the country. By 2013, they were 46 percent of all union workers, and if the current trend continues, they will become a majority by 2025.

The priest of the small parish in Karama town—150 kilometers south of Kigali, the Rwandan capital—directed members of his congregation to offer a sign of peace to their neighbors. Tutsi women sat on one side of the church, Hutu women sat on the other, and they never so much as looked at each other. This moment in the service passed the same way every week for years after the Rwandan genocide in 1994.

The Tutsi women in the congregation were widows from the genocide. The husbands of the Hutu women had raped the Tutsi women and killed their husbands and other relatives.

Months after the genocide, Hutu women had started to return to their villages. Their husbands who had participated in the genocide were in prison either waiting to be tried for their crimes or already serving sentences. When the wives brought their husbands food at the prison, they were stoned by Tutsi women and children.

In 1998, the wives of the perpetrators approached a nun at the church and asked her to arrange a meeting with the Tutsi women. Several dozen Tutsi women agreed to meet. As one of these women recounted years later when Bread for the World Institute visited the community, she was scared and as soon as she entered the church, she wanted to leave. “I saw them as their husbands,” she said. Her baby had been killed by one of these men; for days, she continued to carry the child on her back. The nun who had brought them together said, “You accepted and they are here. This is hard for them as well.”

A Hutu representative said, “We know we didn’t help you when your relatives were being killed, but we want you to listen to us.” The Hutu women had come to ask forgiveness. “It took more than three years to work up the courage to ask for this meeting. We’ve carried around our shame ever since we returned.”

The Tutsi women did not forgive them initially, but slowly their hearts softened. They were caring for many orphans from the genocide, and the Hutu women offered to help them by cleaning their homes, fetching water and firewood for them, working in their gardens, and caring for the children when the Tutsi women had to be away.

The turning point for the Tutsis came when they asked the Hutus to find out from their husbands where their victims, the Tutsi husbands and relatives, were buried. The Hutu women went to their husbands in prison and returned with the information.

The Tutsi women had formed support groups as early as the first months after the genocide to cope with their suffering. Now, they invited the Hutu women to join their groups. “I never thought I would be able to forgive them,” said the woman who had longed to run out of the church at the first meeting. “But I truly forgive them from the bottom of my heart.”

The women wanted their children to learn to get along, and for the first time allowed them to play together. The children have grown up as friends, and recently some of them have married each other.

“Today, we share everything,” explained one of the women. “We live like sisters.” The group continues to expand, consisting of more than 1,700 members.

Word began to spread around the country and to other parts of Africa about these women. They call themselves The Courage of Living. In 2010, The Courage of Living was honored by the national government, and in 2012, the group received a delegation of Kenyan women parliamentarians to discuss ways to reunite Kenyans who remained divided by post-election violence in 2009.

2015 marks the 20th anniversary of the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China, a watershed event for supporters of women’s empowerment around the globe. Twenty years later, the impact of the Beijing Platform continues to reverberate. The conference produced the Beijing Platform for Action, undoubtedly the most influential statement on women’s empowerment to date.

2015 marks the 20th anniversary of the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China, a watershed event for supporters of women’s empowerment around the globe. Twenty years later, the impact of the Beijing Platform continues to reverberate. The conference produced the Beijing Platform for Action, undoubtedly the most influential statement on women’s empowerment to date.

Barbara Howell, Bread for the World’s government relations director in 1995, attended the Beijing Conference. She had also attended two of the three previous U.N. Conferences on Women, in 1980 and 1985 in Copenhagen and Nairobi, respectively. But in Beijing, Howell was struck by an atmosphere of excitement many times more intense than the mood at the earlier conferences. The tens of thousands of women who had traveled there from around the world resolved to “bring Beijing home.”

Barbara Howell tried to bring Beijing home as well, but back in the United States, she encountered a public that was mostly indifferent to the spirit of Beijing. The women Howell spoke to who had not attended didn’t feel any more empowered than when she’d seen them last. Men listened politely but were no more interested in supporting a new era in gender relations than they had been before.

Faustine Wabwire, who is now a policy analyst with Bread for the World Institute, was an adolescent living at home in Kenya at the time of the Beijing Conference. What she remembers is the derogatory treatment of Kenyan women who had attended the conference upon their return. It wasn’t until she was in college, associating with other ambitious young women, that she understood finally how the women who had been at Beijing saw the conference much differently.

2015 brings another moment of opportunity to press for women’s rights in the context of a new global agreement. At the end of 2015, upon the expiration of the MDGs, member states of the United Nations are expected to adopt a framework that will serve as the successor to the MDGs and include new global development goals. Much as the MDGs were the focus between 2000 and 2015, the new goals (whose anticipated name is the Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs) will set international development priorities through at least 2030.

The Beijing Conference and all it stood for belong to 1995—although its goals remain alive. As we look to this new opportunity, it is time to get serious about empowering women and girls. We laud the progress of girls attending primary school at the same rate as boys—and yet we overlook the one in nine that are pulled out of school and forced to marry. We understand how important women farmers are to feeding the world—and yet we act indifferent to how much time they have to devote to drudgery. We do what we can to empower them with policies and programs, while resisting the fundamental nature of the problem, the discrimination they face. Let’s seize this opportunity to get it right for women here and now and for future generations who will live in a world without hunger.

NASFAM, the National Smallholder Farmers’ Association of Malawi, is the country’s largest farmer organization with more than 120,000 members. Women’s empowerment is one of NASFAM’s main priorities, but empowerment programs can—and some would say “must”—work with men to address gendered norms that hold women back. Farming presents a natural opportunity to work with husbands and wives because it is something they both do. Whether they are working together in the same field or separately, it is their combined production that goes into putting food on the table and keeping a roof over their heads.

Connex Malera initially resisted his wife Dyna’s appeals to attend a meeting of the producer group she had joined. But after he consented and attended one meeting, he could see that working within a group had its advantages. What happened then is something he didn’t expect. NASFAM offers farmers training in running an agribusiness; as part of the training, instructors help participants examine gender dynamics in their household and how these dynamics affect their ability to achieve their business goals. By working together with his wife on a vision of what they wanted to accomplish together, he was in a sense forced to listen to her ideas about farming, and it was a surprise to him how smart she is—smarter than he is, he thought.

“I used to say this is a wife and her job is to cook and take care of the children,” Connex told Bread for the World Institute at a meeting with the producer group. “I am the head of the household and it is my job to make all the decisions. Now we discuss and make decisions together.”

The value of having men in the group extends beyond the changes in the male participants themselves, because they become ambassadors for change among other men in the community. They have more credibility than women do when they make the case to other men for suspending their biases against working with women. Connex recruits other men to the group now. But he does this in subtle ways, often talking with them at informal gatherings where they may be playing a board game or drinking. At first, the other men dismissed his argument that there was any benefit to working with women. Eventually they grew curious: first after noticing that his income was rising, and then when the hungry season came and he had plenty of food while they were running out.

One of the men Connex recruited was Sungani Selemani, who recounted how he used to share Connex’s attitude that it was useless to discuss business with women. Today, he has joined the group with his wife, and they discuss all of their household matters and make decisions together. In addition, he says, he has quit drinking and stopped hitting his wife when he is unhappy.

Yusef Dickson has also quit drinking and says that the group has helped him to become a better husband and father. A musician, Yusef has composed a song about his transformation. And when we spoke with him, he also shared a story about how the training they have participated in together has also changed his wife. “After she had sold her groundnuts, I had not yet finished with my tobacco. She came to me and said take this money and use what you need to finish your tobacco. That taught me a lot. Previously, she was just like me—keeping the money she made from her groundnuts for herself. All the money I made from my tobacco I kept for myself. She never knew how much I made and I never told her. Now we share everything we earn.”